More building rights, more planning flexibility, and most importantly – an attempt to encourage municipalities to implement urban renewal on a larger scale than ever before. Only one month after being appointed Minister of Interior, Ayelet Shaked presented a new urban renewal plan that she hopes will replace Tama 38 and increase the number of projects of this nature.

Just one month after the inauguration of the new government, the new Minister of Interior, Ayelet Shaked, already proposed a replacement plan for Tama 38 (The National Outline Plan), which is today considered the most significant government measure to encourage urban renewal construction in Israel. Tama 38 is due to expire in October 2022, and because the current government was so recently sworn in, most expected that the current plan would simply be extended. However, Shaked surprised everyone when she announced a newly-formulated alternative plan in July.

The news of this plan goes beyond the realm of urban renewal, as Tama 38 has also been an effective tool for the mass construction of apartments in the heart of the crowded and sought-after Gush Dan region. During a period of skyrocketing Israel real estate prices and a shortage in the supply of apartments, the expiration of Tama 38 without a replacement plan was expected to exacerbate the crisis in the market.

However, the question of whether or not Tama 38 will ultimately be extended has not yet been decided. MK Shaked announced that in the event that her new plan is not approved within four months of its presentation (by mid-November 2021), she will work to extend Tama 38 by one year, in order to make sure that the country is not left without a plan for urban renewal. It should be noted that if the alternative is approved by this date, there will be a one-year period in which both plans will be in effect simultaneously, until the official expiration of Tama 38.

Slow-moving municipalities risk losing their authority

Shaked’s proposal includes a number of significant changes to Tama 38. Firstly, in contrast to Tama 38 where urban renewal projects require the issuance of a building permit only and without the need for the approval of a city building plan (TABA), the Shaked alternative requires approval for each project by the local authority only. The application process for urban renewal will include the building permits, meaning that once the plan has been approved by the municipality, the developer will be able to start construction immediately, without the need to submit another application for a building permit.

Secondly, in an attempt to expedite the process of the municipal planning committees, Shaked’s plan states that if a certain amount of time has passed and a municipality has not yet discussed a plan submitted for approval, it will automatically be bumped up to a higher court hearing at the District Planning and Building Commission. This clause poses a threat to municipalities; those that do not function efficiently will lose their power to make decisions regarding construction projects in areas under their jurisdiction.

Incentives to encourage municipalities to cooperate

One of the most significant changes suggested by Shaked concerns the incentives given to local authorities to promote urban renewal construction within their municipal boundaries. Up until now, local authorities tried to limit Tama 38 projects, as they are fully exempt from Hetel Hashbacha (improvement levy). The local authorities collect this tax when additional building rights are added to an existing plan. Municipalities use this income to fund the upgraded residential infrastructure required, including paving roads and sidewalks, and building schools and public institutions. Under the current Tama 38 plan, the authorities found themselves in a situation where a building plan permitted the construction of additional apartments, without allowing them to collect taxes to fund the expansion of infrastructure required to properly absorb new residents.

Shaked’s alternative includes two incentives for local authorities. First and foremost, the new plan is expected to allow municipal authorities to collect the improvement tax. In addition, it will allow municipalities to add other projects amounting to 15% of the total area being built under each new urban renewal plan. These additional projects will be designated as public buildings, including kindergartens, daycares, synagogues, and more. This clause enables municipalities to develop new public areas alongside the residential projects.

Greater economic feasibility

Shaked’s urban renewal construction plan makes more economic sense for executing projects, as it grants significantly more building rights than Tama 38; 400% of the existing built-up area for “evacuation and construction” projects and 200% for “reinforcement-expansion” projects. Furthermore, the number of floors will not be restricted, and it will be determined by the local committee.

The plan also allows developers to consolidate several plots into one complex when demolishing old buildings, enabling them to utilize all of the building rights to build a smaller number of taller buildings. For example, a developer can replace four old buildings with two larger towers, then use the rest of the area for other purposes, such as gardens or public areas. Tama 38, on the other hand, used the building-for-building method, where the plots were not allowed to be redesigned for other purposes.

The periphery is still left behind

Although Shaked’s new plan improves many of Tama 38’s shortcomings, it has received mixed reactions in the planning and construction industry, with experts pointing out that some of the old plan’s major failures were not addressed.

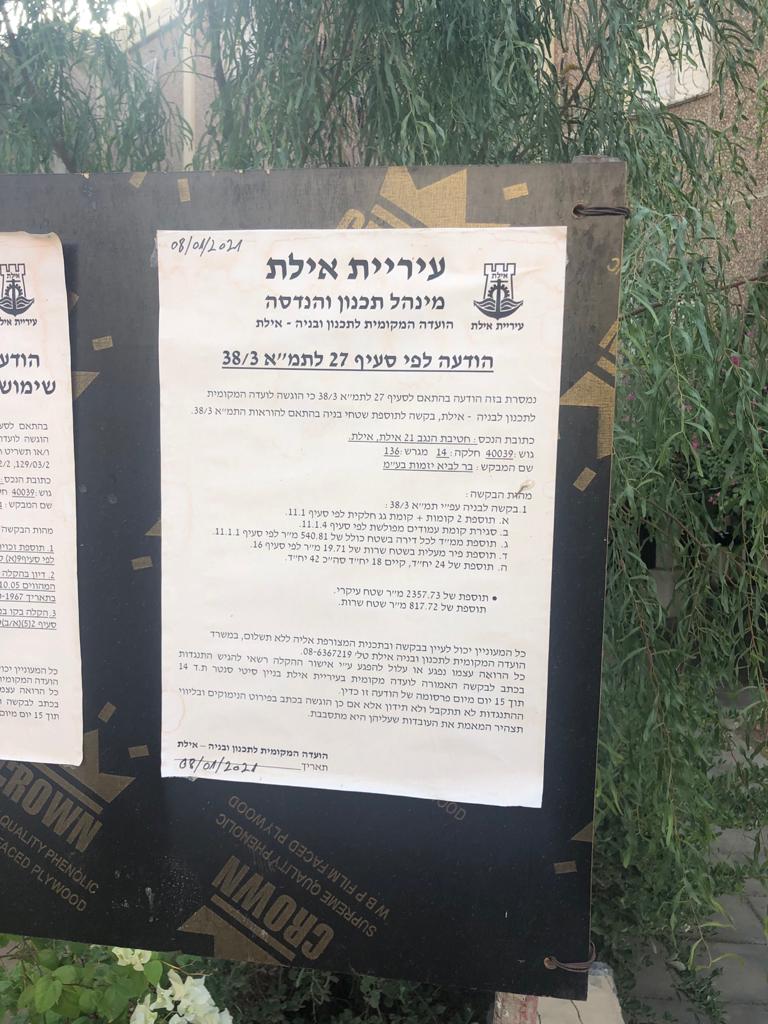

The most obvious of all is the fact that Tama 38 was rarely implemented in peripheral areas due to a lack of economic viability. Despite the fact that more remote cities such as Tiberias, Beit She’an, and Eilat are situated along the Syrian-African Rift, where there is a significantly higher risk of earthquakes than other regions, Shaked’s new plan does not in any way encourage construction of urban renewal projects in these areas. If this plan is approved, it seems that the vast majority of urban renewal projects will continue to be built in the central cities of Gush Dan.